3. My Father's Birth Certificate

In which I make two Proustian discoveries, one relating to Virgina Woolf in Cornwall, and the other, a lost family grave…

My Father’s Birth Certificate

Not even my agents nor my husband follow me on Substack yet but this newsletter contains a discovery AND a quest (who doesn’t love a quest) so one can only live in hope.

When it comes to the future none of us know what happens next, even if we do know how it ends (unless you are the Redeemer, who liveth). But when it comes to memoir, history, paperwork and documents are all key – hence this Substack - but it does also help to ask someone you know who knows.

This is harder than you think.

My husband’s father, Captain Oliver Dawnay, came back from Normandy in WW2 as a young man after watching his brothers in arms burn alive in tanks. He never spoke about it, and died in his sixties. I never met him.

My grandfather had two almost fatal plane crashes in the war. I adored him. He had one leg much shorter than the other after his crashes and plastic surgeries but never complained, nor mentioned the war. He drove me to Bryanston on my first day at school, aged 13. We drove from Exmoor to Dorset in the Land Rover Series 2 Defender (1971 model) which was slow going then (and slow and still going now).

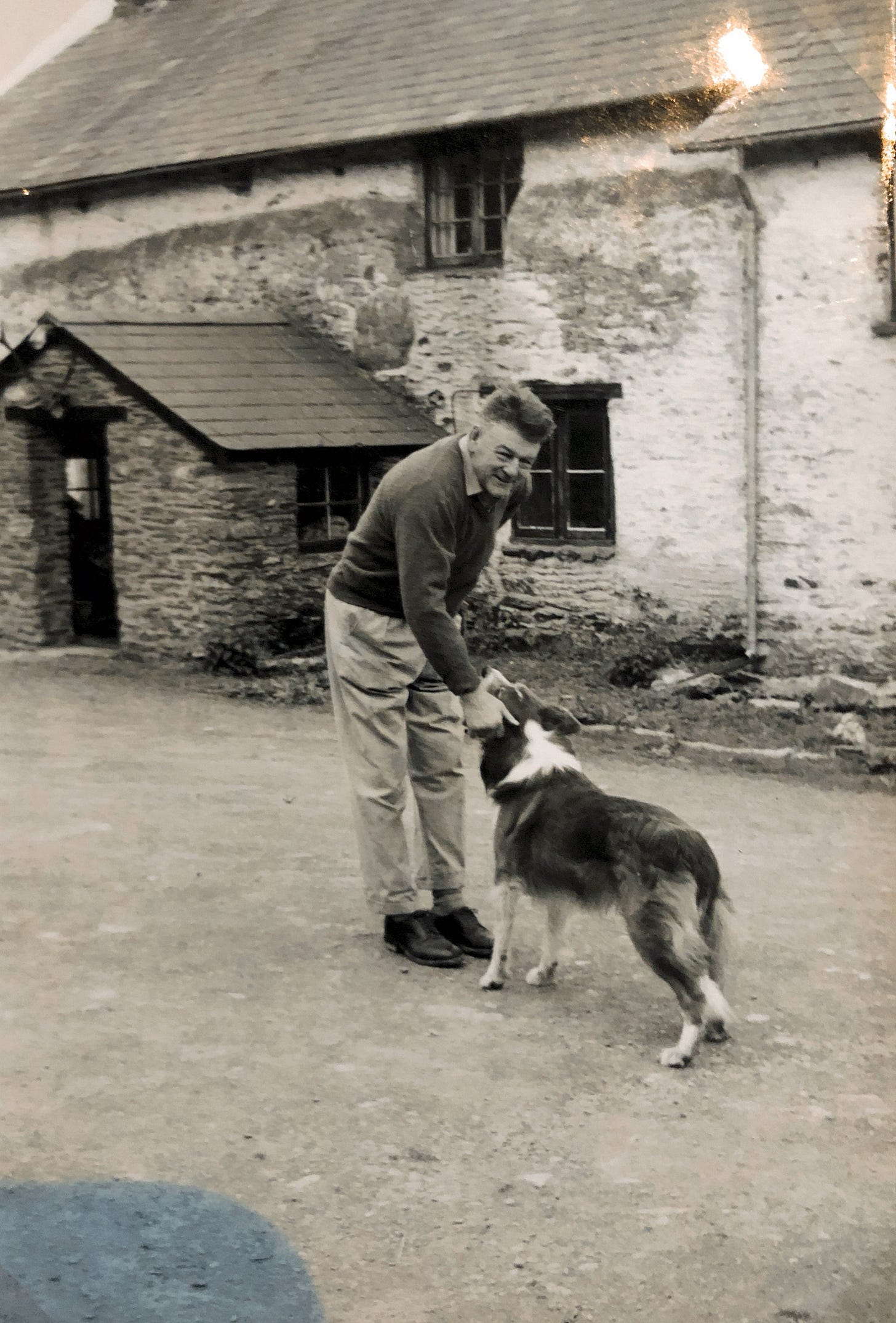

He dropped me at my boarding house, Purbeck, keeping the engine belching. “Here you are Spider,” he said, tapping his pipe out on the driver door, “I can’t turn the engine off and come in as I won’t be able to get her going again.” I pulled my trunk out of the back and it crashed to the ground and he backed out of the courtyard past all the other mummies in tiered skirts (well it was 1979) and daddies at the wheel of Volvo estates. Those were the days. I could have asked him all about it in those hours bumping across the West Country, with his terrier between us, but I didn’t. Here is a picture with him in the yard with one of the sheepdogs.

.

Not only did he never mention the war, he never mentioned once that he was born Osman Ali, he was an orphan after his mother died in childbirth, and his Turkish father, a politician and journalist, murdered by a mob and his body parts hung from a tree.

He just got on with his life. As far as he was concerned, and as far as everyone else should be concerned, he was an Exmoor hill farmer, Johnny Johnson, and he had his own special chair by the fire in the pub, the Royal Oak, Winsford.

I now wonder if anyone ever asked him about his war, and who regrets not having done so. I know I do.

For the latest episode of my Difficult Women podcast, I’ve just interviewed the historian Anne Sebba, who knew her father, Major Eric Rubinstein, had arrived at Bergen-Belsen just after the liberation of the death camp by the allies. “But he never talked about it,” she said.

For her 70th birthday, her son handed her a slip of paper, with a reference number for a file in the National Archive.

It was for her father’s file. Anne Sebba found in it a summary for his War Diary for May 24, 1945, and an entry, which ran, “C Squadron 7R Tanks burning Belsen camp with Crocodiles.”

Decoded, this meant her father’s squadron was using flamethrowers to purify the lice-ridden huts. “How could I call myself a historian and missed this story,” she berated herself. The result of her quest is her new book The Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz (the remnants of the WOA ended up in Bergen-Belsen). “I was gripped by a need to find out how these women survived,” she told me.

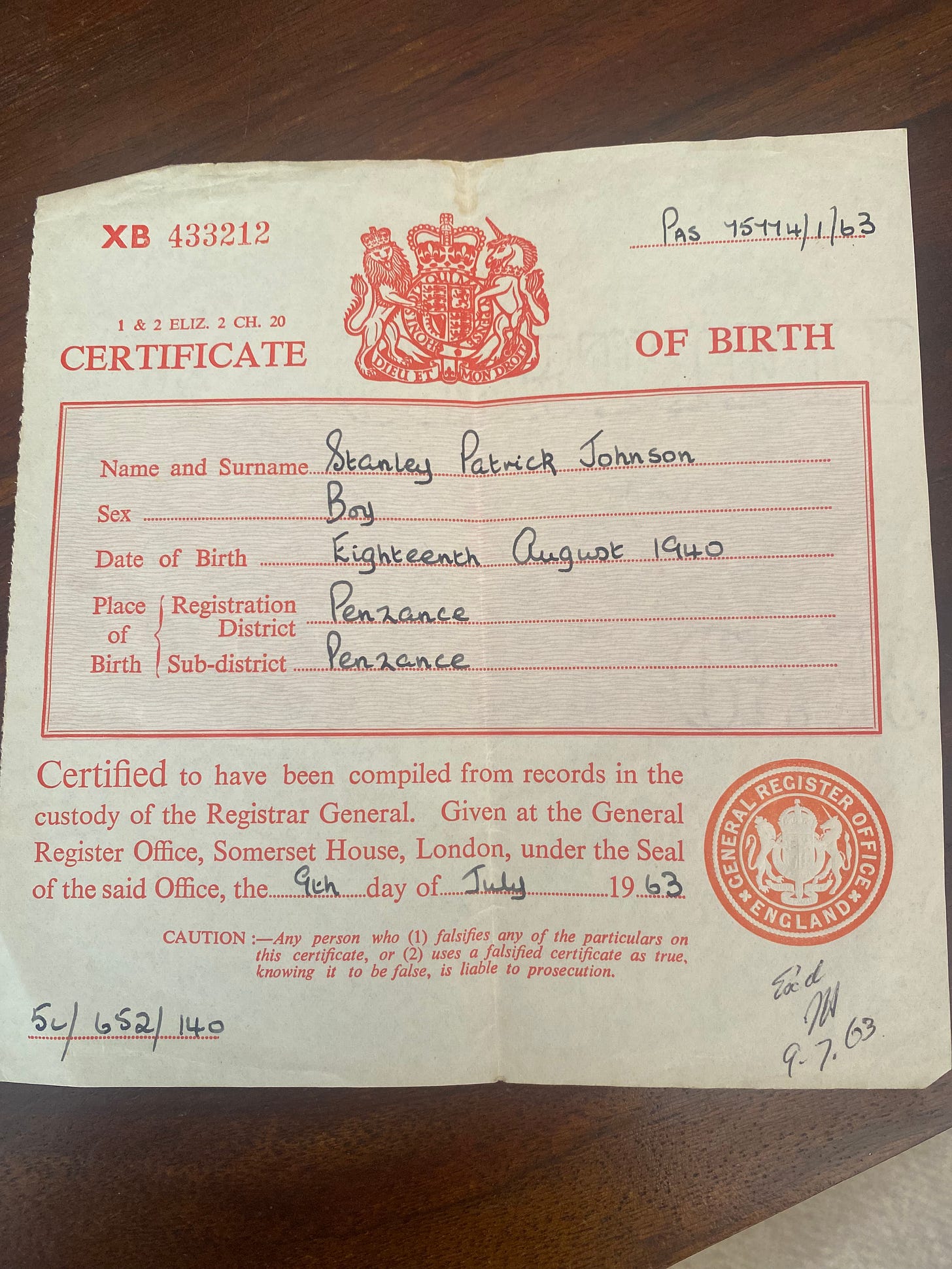

My father is very much alive and even though my own birth certificate is still missing I went to ask him about his, which I showed him on Easter Sunday in the middle kitchen of his mediaeval farmhouse on Exmoor.

.

He immediately spotted as I hadn’t that it wasn’t an original, but a copy, as it was dated 1963 and he was born 1940, during the war. And thereby hung a tale.

I knew that his father, my pictured grandfather, above, who flew Wellington Bombers for Coastal Command, and earned the DFC, was based during the war in Chivenor, Devon.

His mother, though, my Granny, was staying at her father’s house, a detached villa with a sea view called Trevose View, on Carbis Bay. It was there that she suddenly went into labour. Poppy, her father Stanley’s Rolls Royce, had been decommissioned during the war. Poppy was put back into active service for the important service of conveying her to Penzance General, where she was safely delivered of son on August 18, 1940.

Now here things get interesting.

During the G7 summit in 2021 hosted by my brother as UK PM at Carbis Bay, there was a certain amount of interest in why the summit had been held on the Cornish riviera. Reporters put two and two together, joined the dots, to find the story. A reporter from the Daily Mail went to Trevose View and “knocked up” John Bestwick, the then owner of my great-grandparents house, and he told the man from the Mail “the house was built in 1899 by the captain of a tin mine and Virginia Woolf certainly stayed here while she was writing her novels.” Hold that thought.

Back to my father’s post-dated birth certificate. Had he lost his original, as I have mine? I asked. Why would he need it in again 1963?

“Ah, because we were moving to America,” he said. “You didn’t need it as a marriage requirement too?” I asked. (My mother and father married in 1963 in Marylebone Registry office, but I knew my mother had demanded a later second ceremony in New York, at St Jean Baptiste on Lexington and E 76th, with the Rev Wilfred Thibodeau of he Fathers of the Blessed Sacrament officiating. She was terrified that if she died in childbirth she would burn in the hell-fire and so would the baby she was due to have in 52 days unless the marriage had been consecrated in the Catholic church). “Er, no,” my father - an agnostic - said.

At which point I switched off the recording and said I had to go to Cornwall, to stay with the Swires.

(Sasha Swire of course has written the erudite and connoisseur’s version of the Salt Path, called Edgeland and her father was the local MP Sir John Nott.)

I said this as we all love Cornwall, we Johnsons, and of course, he was born there, as above, and anything that relates back to that, or the natural world beyond, is of interest, and he was interested.

“Oh, the Nott place,” he said. “Lelant. I used to go to Sunday School at the church there, on the headland. And,” he went on, “My grandparents, who lived at Trevose View are buried there, of course. But I’ve never found their grave. Nor did Birdie and Hillie,” he added (his sisters). Here is a photo of Stanley with his older siblings Pete, Hillie, and my grandmother Irène and a Dalmatian, for reference. Birdie had not been born yet.

.

We were standing in the yard. I was clutching his shiny hardback copy of Exmoor Farms A Year on the Moor which I was borrowing and a mug of tea.

“You’ve never found the graves?” I asked. It didn’t seem possible. “When did they die?” He told me his grandmother Marie-Louise died in 1944 aged 62, and his father Stanley died aged 75 ten years later.

There’s nothing I like more than a challenge.

I set off from Exmoor to Cornwall in search of the lost graves of my ancestors.

Later that afternoon I was in Lelant’s St Uny church, set on a chunk of headland a way out of the village. The church can be approached by the yellow-sand beach, like crumbled fine shortbread, and the sea, or via a shady lane.

The grey Norman church, I noted, was surrounded by no less than three large graveyards, with acres of innumerable gravestones with markings weathered indistinct by the rough winds and sea air. We had our work cut out.

Sasha Swire leant on a granite waymarker with a cross, one of the many placed to guide the saints from Ireland to the heathen and told me about St Uny and the Christian immigrants from Ireland who brought the holy word across the water.

Then we got down to it.

“We should divide the church into sections like the police doing a fingertip search for Nicola Bulley,” I said. We did one graveyard first. Sasha went off to the right and I did a middle section. Nothing. I was beginning to lose hope of finding Marie Louise or Stanley.

After ten minutes, an exultant cry. I rushed over.

“I’ve found Peter Lanyon’s grave,” called Sasha, her blonde head bobbing between the bluebells.

It was indeed a magnificent granite slab, with a rectangular slate with a delicate, etched inscription:

I will ride now

The barren kingdoms

In my history

And in my eye

“This is much more interesting than your great grandparents,” she crowed, correctly.

I mean, there is nothing more stupefyingly boring than other people’s relations. Who has ever studied a branching family tree at the beginning of a biography with any relish? Who hasn’t longed for a story to start not with the subject’s ancient ancestors but at the point at which this person becomes interesting? David Cameron had to cut out endless pages from his autobiography about his time at prep school, he told me, a period of life which held a deep meaning for him but nobody else, apart from his perhaps his siblings, and his parents. So I know I may be testing the limits of endurance of my readers here (feedback welcome…)

Sasha told me about Lanyon: his paintings were in Tate St Ives, he was the leading light of the St Ives school (I Googled him and found how he died in a gliding accident aged just 46 in the vale of Taunton, which has no views at all). “This is how I want to be buried,” Swire said, noting the granite tomb, adorned with the slate slab, so I took a picture for her husband Hugo and daughters, for reference.

Just as I was doing so, out of the corner of my eye I saw the words: Marie-Louise.

Two graves to the left of Lanyon.

Not only my great-grandmother, but my great-grandfather, and even my great aunt, known as Tante Yvonne. All in one grave. With their dates. There was an inscription in French (my grandmother’s first language).

‘Le vaisseau qui portait toute ta fortune est entré dans son havre de grâce au jour levant'

It was only later, when I was talking to my aunt Birdie, an aural historian, who had also tried and failed to find the grave (pictured below) that I understood. I had been standing exactly where my grandmother had stood when she buried her mother in 1944 (pregnant with her fourth, Birdie), her father in 1955, and lastly her aunt, Yvonne de Pfeffel.

And then my aunt Birdie sent me all the pages of the letters of Virginia Woolf that mentioned Trevose View, the house that Virginia and her Stephen siblings stayed, played, wrote and painted in the early part of the last century, and to where in 1940, my grandmother returned with my newborn father in her arms.

Woolf wrote of Trevose View like a schoolgirl with a pash.

“This is a divine place” and has the “divinest view in Europe” she wrote in her many letters from Trevose View in 1905, to her friend Violet Dickinson (Virginia Woolf: The Complete Collection).

“I find it so difficult to write here and must set to work tomorrow,” she wrote to her friend one delicious August, adding her maybe because she lived in “perpetual lovemaking and giving in marriage.” In one letter to a friend – addressed to “Todger,” and signed “Goatus” - she rhapsodises about “moors, seas, hills, rocks, the land flowing with cream as well as a honey; that “Nessa” – her sister, Vanessa Bell, is painting away; and that she is writing hard, daily, from 10 to 1.

I’m going to stop there, as this is a minor personal triumph that I don’t expect anyone not called de Pfeffel, Williams, or Johnson (and certainly not my husband or agents) to share.

I wish I’d gone to Trevose View. But I didn’t have a car. That will have to wait.

So instead of seeing the house and the view to Godrevy lighthouse, and Trevose Head, from which Woolf salted away memories to write her three sea-based novels – Jacob’s Room, The Waves, and To the Lighthouse - I got the train that goes backwards and forwards all day long from St Ives to St Erth.

In 1905 Trevose View was perched behind the Carbis Bay hotel and on its own, unsurrounded by other houses.

As I settled into my seat for the fifteen minute Corniche ride from St Ives to St Erth, when we rattled through Carbis Bay, suddenly the vistas of yellow sands and sparkling waters were obscured by some undistinguished post war housing and I couldn’t see the sea at all.

Two postscripts. My father says he HAS my birth certificate! But if it is still missing, and I still need it for something (I can’t think why) I can order a copy, just as he did in 1963. My husband has just read this and complained it was uninteresting, thus proving my point about other people’s relations. I have thanked him for his helpful feedback and will bear in mind for future Papers!

Astonishing how much your father as a child looks like Boris

Sitting in bed on a Sunday morning with a cuppa and Google maps zooming in on places mentioned … I loved this read Thankyou